Boethius and Early Medieval Logic

From the fall of the Roman Empire around 500 AD until around 1100, the logic of the ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, along with other core disciplines, formed the foundation of the only education to endure through these centuries, primarily as a preparation for the reading and study of the Bible in monastic schools, and it continued to do so even after the founding and development of the new institution of the university in later centuries (from about 1100 to 1500 onward). These basic subjects were known as the Arts or Liberal Arts and consisted of Grammar, Logic, and Rhetoric (the Trivium), and more advanced quantitative studies of Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, and Music (studied mostly for the mathematical aspects of harmony). These latter four subjects made up the Quadrivium, a term coined by Boethius, whose translations of ancient texts on logic, especially those of Aristotle, along with ancient commentaries on them (as well as Boethius’ own) served as the basic textbooks of logic throughout the Middle Ages. Boethius likewise wrote texts on music and arithmetic which were also foundational for these subjects.

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (d. 524 AD) was a Catholic layman and the scion of an ancient Roman family, and when Theodoric the Ostrogoth, an Arian (i.e., non-trinitarian) Christian, took control of Italy and sought to maintain the vestiges of the western Roman Empire, Boethius served the Gothic king and worked to preserve Roman and classical culture and learning in this new era of barbarian rule. The political career of Boethius, however, did not end happily.

Theodoric accused Boethius of plotting against him on behalf of the eastern [Byzantine] empire and sentenced his faithful political servant to death. In Pavia, awaiting execution, Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, the most circulated work after the Bible in the early Middle Ages. In this magnificent work, which alternates poetry and prose, Boethius asked, in effect, how an innocent man like myself should have ended in such a plight.[1]

Though he intended to translate all of the works of Plato and Aristotle from Greek into Latin, Boethius only succeeded in producing translations of Aristotle’s logical treatises, with commentaries on some of them, in addition to an important introduction to Aristotle’s Categories by another ancient writer, Porphyry. He also wrote logical treatises of his own based on the works of Aristotle; however, not all of these works were known in the early medieval period. Below is a list of the logical works translated and commented on or written by Boethius; the ones marked with an asterisk (*) were known before around 1120:

- Aristotle

- Categories*

- On Interpretation*

- Prior Analytics

- Topics

- Sophistical Refutation

- Porphyry

- Isagoge (introduction to Aristotle’s Categories with two commentaries) *

- Boethius

- Introduction to Categorical Syllogisms*

- On Categorical Syllogisms*

- On Hypothetical Syllogisms*

- On Division*

- On Differences in Topics*

The Rise of Universities and the Faculty of Arts

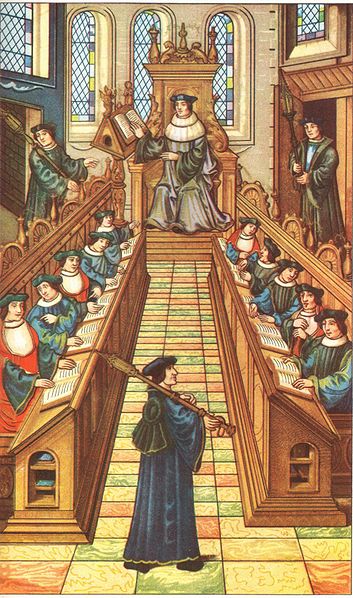

As cities were established and grew throughout the high medieval period, universities were founded and developed with these new, thriving, and forward-thinking (compared to medieval feudal estates and monasteries) urban centers of Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Cologne, and Naples. The new universities nevertheless continued the tradition of grounding education on Aristotle’s logical works, and so organized their teaching and courses of studies into the Faculty of Arts as a preparation for higher studies in the Faculties of Medicine, Law, and Theology.

The studies in the Arts were thus the core of medieval logical, linguistic, and philosophical studies any scholar had to master in order to be admitted to ‘graduate’ studies in the higher faculties. Most medieval university students were priests or lesser clerics in the Catholic Church and pursued these higher degrees for practical, professional reasons, i.e., to pursue a career practicing law, medicine, and clerical preaching and administration, though an elite of these stayed in the university as professors and faculty to train future generations of scholars. Though the studies in these institutions of learning were based on logical works of Aristotle, these were just a relative few of the many more he produced. When other works of Aristotle were “discovered” in the 11th and 12th centuries by scholars in Western Europe through contact with Muslim and Jewish texts and authors in Spain, southern Italy, the Holy Land, and Byzantium (in part because of the Crusades), it fell to the Faculty of Arts to study, teach, or comment upon them. These “new” works of “the Philosopher” (as Aristotle was called by Saint Thomas and most other medieval thinkers), included works on natural and philosophical topics, many of which would eventually develop into modern experimental, sciences.

- “New” Logical Works

- Prior Analytics

- Posterior Analytics

- Natural works

- Physics

- On the Heavens

- On Generation and Corruption

- Meteorology

- On the Soul

- Short Natural works (Parva Naturalia): On Sense and Sensible Objects, On Memory and Recollection, On Sleep, On Dreams, On Divination in Sleep, On Length and Shortness of Life, On Youth and Old Age, On Life and Death, On Respiration

- Biological works

- History of Animals

- Parts of Animals

- Movement of Animals

- Progression of Animals

- Generation of Animals

- General philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Practical philosophical works

- Nicomachean Ethics

- Eudemian Ethics

- Politics

- Literary Theory

- Rhetoric

- Poetics[2]

It may seem strange that medieval thinkers first had to pursue and master ‘arts’ before going on to what they considered higher sciences, subjects that hardly seem scientific to us. In fact, those subjects we consider ‘sciences’ developed out of the medieval Arts Faculty, especially the more mathematical of them. The term ‘art’ has retained for us the notion of making, and the artist is one who has the art – experience, insight, and skill (internal properties of the artist) – to fashion matter according to their intention and goals (beauty or meaning or profit). Thus, painters, sculptors, architects, woodworkers, etc. are artists, but they are bound by the physical media in which they work. In the Middle Ages, the idea of artists was broader and meant primarily, not the product or work of art, but the internal property of the person to create anything whatever, even things free from matter like speech, arguments, or stories.

Thus, these seven subjects (Trivium and Quadrivium) which comprised the core, basic learning of university Arts Faculties came to be known as the Seven Liberal Arts, since they taught students the art, the internal disposition or habit in their minds, for making products free from matter, hence ‘liberal.’ (Later thinkers added that such arts helped make a person ‘free,’ self-governing and autonomous, capable of building and participating in a free society.) In that the liberal, like manual or servile, arts were directed to making a product, the medievals considered them ‘practical.’ But, the product of logic, at least, was something non-physical, i.e., understanding or knowledge, and this, the medievals believed, need not be directed to anything else.

This knowledge they called ‘speculative’ or ‘theoretical’ (as opposed to ‘practical’), meaning not that it is uncertain or fanciful, but that it is knowledge simply worth pursuing and contemplating for its own sake. When this knowledge resulted from a logical process, the medieval thinkers considered it to be science (scientia in Latin). Science, as we will see below, was grounded in and directed toward more basic and exalted forms of knowledge, understanding (intellectus), and ultimately toward wisdom (sapientia). It is thus essential to and constitutive of the love (philia in Greek) of wisdom (sophia), i.e., philosophy.

[1] Ralph McInerny, Aquinas (Polity 2004), p. 6.

[2] Bernard G. Dod, “Aristoteles Latinus” in The Cambridge Companion to Later Medieval Philosophy, edited by N. Kretzmann, A. Kenny, and J. Pinborg, (Cambridge UP 1984), pp. 45-79.

Return to Logic – Overview – Next: Art of Logic and Science of Reason

Please support the Thomistic Philosophy Page with a gift of any amount.

Updated January 18, 2025