Thomas Aquinas along with Aristotle begins with the conviction that all human knowledge arises from sense experience and that no knowledge is innate or inborn to human beings. We are, instead, born with the ability to draw from our experience of sensing material particulars knowledge that is universal, rational, or intellectual, these being different ways of characterizing the kind of knowledge distinct from sensation. In this, Aquinas, like Aristotle, rejects Plato’s account of knowledge wherein we are born with an understanding of the universal natures of things.

Aristotle recounts at the end of his logical works how we arrive at this universal knowledge through a process he calls induction, and it arises from sensation, memory, and experience:

So out of sense-perception comes to be what we call memory, and out of frequently repeated memories of the same thing develops experience; for a number of memories constitute a single experience. … We conclude that these states of knowledge are neither innate in a determinate form, nor developed from other higher states of knowledge, but from sense-perception. It is like a rout in battle stopped by first one man making a stand and then another, until the original formation has been restored. The soul is so constituted as to be capable of this process.[1]

From the experience of many particular things one retains memories of them and naturally groups similar memories of individual things into experiences of groups of things according to their similarities; this “constitutes single experiences.” For example, from the memories of perceptions of particular individuals Fido, Spot and Lassie, one develops a common experience of barking, fetching, four-legged, furry animals in one’s memory. And from the experience of many dogs, one grasps the universal species of dog, of which each of the individuals is an instance. By reasoning inductively from many individuals grouped together in experience, one comes to a knowledge of what is common to them all, or the universal class or kind to which they belong. Thus, through induction, the mind forms concepts which one expresses in words or terms. As we will see below, the first task of the art of logic is to order this act of simple apprehension or grasp of simple concepts (indivisible or uncomplex things, as Aquinas says above) by producing good definitions using the predicables of genus, species, difference (discussed below) to specify the relations among concepts and the classes of things known through them.

Words, Concepts, Things

In the logic of Aristotle used by Thomas Aquinas and the rest of the philosophers and theologians of the Middle Ages, one must concern oneself with words, either written or spoken. But it was universally understood that written words represent spoken words, and that both kinds of words signify concepts in the mind, which are themselves somehow universal, referring to groups of many individual things in the world. And so concepts, like words, signify the things so referred to. Indeed, words only signify things through concepts, and apart from a mind who understands the word, a word is just a physical object – a vocal sound, or marks on paper or dark or light pixels on a screen, or meaningless hand gestures (unless used by minds in sign language).

There are three kinds of words, or three ways words can signify, which are important for understanding Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. The meaning of a word may be

- Univocal – one word has one meaning, though more than one word may have the same univocal meaning. For instance, “wood” (generally) has one meaning, i.e., material derived from trees, but other (synonymous) words may have the generally same meaning, such as “lumber” or “timber.” Words with more than one meaning (equivocal or analogical terms) may be used univocally if one clearly specifies how one is using the word. Since the art of logic orders our thinking so we can do it well to attain truth, it is important to be clear about the meaning of terms, and to use them consistently to signify things clearly as they are in the world.

- Equivocal – one word has more than one meaning, such as “bark” which may mean the outer layer of a tree’s trunk, the sound a dog makes, or a kind of small boat (these are all homographs since they are spelled the same; words that sound alike are generally called homonyms or homophones, the two terms being synonymous). In logic, it is very important to be clear that the meaning of terms remains consistent, and one does not try to draw conclusions from words that are equivocal, that is, that have two or more distinct meanings.

- Analogical – one word has several related meanings. Generally, there is a primary meaning to which the other uses of the word are related. A favorite example for Thomas Aquinas is the word “healthy” to describe a person, food, or her complexion. In this case, a person whose body is fit and in good physical condition and can function well is the primary meaning of healthy, while the food is called healthy as contributing to that person’s healthy state, and her complexion is called healthy as a sign or effect of being in that state.

Forming Definitions

The next step in developing the art of logic or the science of reason is to specify how we can gain clarity about what it is we know through induction or simple apprehension, the universal concepts we grasp. We do this by developing good definitions. A good definition will apply to all members of the class signified by the concept, only members of that class, and specify what distinguishes this class from others.

To form definitions, Aristotle introduced the concept of Predicables which are the different ways a term can be said of, or predicated of, many things. They are not what is actually predicated (those are called Predicaments (or Categories) below), but they refer to the ability of different terms to be predicated. Since the universal terms are what can be predicated of many things, we can say that the predicables are different ways of being universal.

There are five predicables, though only the first three are used in making a proper definition:

a. Genus – what many species have in common, and so it designates a more universal class to which many different kinds of individuals belong.

b. Species – what many individuals of the same kind have in common. This is what the definition names, and it expresses the ‘quiddity’ or ‘whatness’ (from quid (‘what’ in Latin) of things, the essence or nature by which the individuals are members of a given class or category. (More about essence and nature in Chapter 3.)

c. Specific Difference – what naturally separates the many individuals in a species from other kinds or species under a given genus.

d. Property – what belongs properly, or only, to one kind of thing, but is not its essence; a property is a feature that all members of species have, such as all humans have the ability to laugh or to use language. The ability to laugh or speak is not part of what a human being is.

e. Accident – what belongs to a thing, but not uniquely. An accident is a feature that belongs incidentally to a thing, i.e., it does not indicate the kind of thing of which it is predicated, and it may belong to other kinds of things. The color brown or black is not unique to dogs; dogs may have other colors, other things may have those colors, and what color it is is incidental to what a dog is.

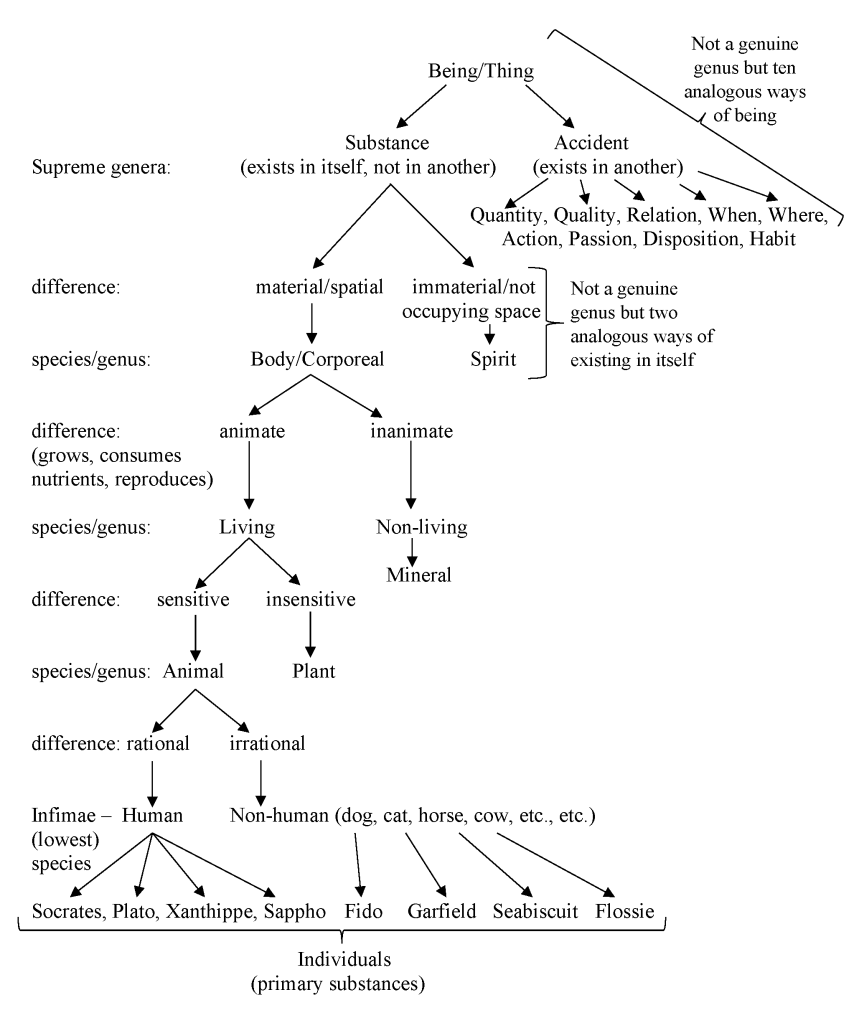

Genus and species are correlative. A given species may be a genus for more particular species below it, and a given genus may be a species of some higher genus. As we will see below, the genus/species ‘living thing’ is a species of the higher genus ‘body,’ and the genus for the species ‘animal’ and ‘plant.’ Ultimately, there are the supreme genera of substance and the nine accidents, and though it is tempting to say there is a higher genus of Being or Thing, in actuality these two ways of being are not really of the same kind, but only analogous to each other. As Aquinas says in On the Principles of Nature, Chapter 6,

substance and quantity do not agree in any genus but only according to analogy, because they are alike only in being. Being, however, is not a genus since it is not predicated univocally, but analogically.

Likewise, the lowest species are genera to no species below them, but there are only individuals belonging to these species.

Definitions ideally identify or express the concept of a species, what it is that all individuals of a given natural kind have in common, and are formed by naming the genus to which the species belongs along with the specific difference.

A good definition must include, i.e., state or signify, what the things defined have in common, one feature that applies to everything that one is defining in virtue of which they belong to the same class, and it must exclude those things not defined. The species is what is common to its members, belongs only to its members, and is the reason why they are members of the same kind or class. The species answers the question, ‘What is it?’ (hence quiddity). The genus is what all members have, but is also had by other classes or kinds of things. The difference excludes everything of a genus which does not belong to the species. Thus, the definition of a species is made by combining a genus and a specific difference. For example, ‘human being’ names all members of the class ‘animal’ which are differentiated by being ‘rational,’ their specific difference. Thus, ‘human being’ is defined as ‘rational animal.’

Porphyrian Tree

Porphyry delineated the various genera differentiated into species or sub-genera which completely define the species human beings. This has been called the Porphyrian Tree, which gives a good overview and illustration of how definitions should ideally be formed.

[1] Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, Book II, Chapter 19 (100a3-14).

Previous: Art of Logic and Science of Reason – Return to Logic – Overview – Next: Logic – Problem of Universals

Please support the Thomistic Philosophy Page with a gift of any amount.

Updated January 18, 2025