Friar, Priest, Philosopher, Theologian, Poet, Mystic, Saint

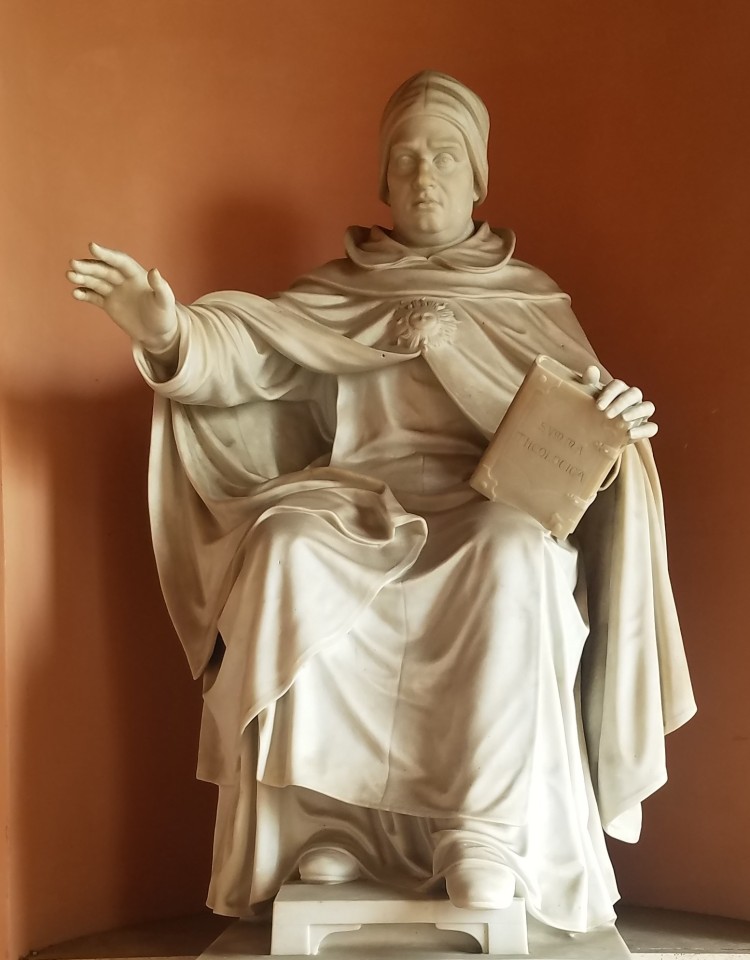

Saint Thomas Aquinas was a 13th century Dominican Friar, philosopher and theologian. Named a Doctor of the Church and given the title “Angelic Doctor,” he is the patron of Catholic universities, colleges and schools. Renowned for his proofs for the existence of God, Aquinas believed that both faith and reason discover truth; a conflict between them is impossible since they both originate in God. Aquinas defended the use of philosophy, especially in the works of Aristotle, as legitimate and beneficial within Catholic theology. In the 13th century in which he lived, this was quite controversial, and the fact that it may not seem so today is a testament to the ultimate positive impact that he had on the Christian Church, and on the wider intellectual world as a whole. He was instrumental, therefore, in the assimilation of the works of Aristotle into the intellectual life of Western Christendom.

Thomas Aquinas was born in 1224 or 1225 to aristocratic parents, the youngest son of Landulf, Count of Aquino, and Theodora, a noble woman of Naples. At the age of five, he was placed in the Monastery of Monte Cassino, in what is today central Italy, to receive from the monks there an education to prepare the young nobleman for a career in the Church. Because of the promise he showed in his studies and because of the conflict that erupted between the pope (to whom the monastery was subject) and the German emperor (whose vassal Landulf was), at around the age of fourteen young Thomas was sent to the University of Naples to continue his education in the Liberal Arts, and there he excelled under his new masters and was probably first exposed to the recently rediscovered natural and metaphysical works of Aristotle, the 4th century BC Greek philosopher and proto-scientist. In Naples, the young Thomas also encountered Dominican friars of the Order of Friars Preachers.

The young Thomas Aquinas was apparently impressed by the spirit of contemplation and preaching, humility, poverty, and service embodied by order of Saint Dominic, and in Naples, at about the age of nineteen, he soon joined the preaching friars. The aristocratic family of young Thomas was not pleased with this choice, however, since the poor and itinerant friars were not held in very high esteem. When his mother set out for Naples in order to retrieve Brother Thomas from the clutches of the Dominicans, the friars sent him to Rome, but Thomas was captured by his brothers, knights in the Imperial Army. He was taken to a family castle and imprisoned for over a year as his family tried to dissuade him from carrying through his resolution to continue as a Dominican.

His brothers even sent a prostitute into his cell to tempt him away from vows of religion with carnal pleasures, but Thomas drove her away with a burning brand. As his confessor revealed years later during the processes of canonization by which he would be declared a saint, young Brother Thomas then drew a cross on the wall and knelt in prayer. After acting so to preserve his chastity, he told his confessor that he was visited by angels who bound him with a blessed cincture which preserved him ever after from temptations of lust. While in prison, he continued his study, and when finally released, he professed his vows in the Order of Friars Preachers.

At the age of twenty, he was placed under the instruction of St. Albert the Great, first in Paris and later in Cologne. Albert was born in Swabia in Germany around the year 1200 and studied at the University of Padua where he encountered Dominican friars and entered their order. He went to the University of Paris to continue his studies, received the degree of Master of Theology, and helped to introduce the newly discovered natural, metaphysical, and ethical works of Aristotle into the university curriculum. Albert also established and organized the Dominican House of Studies in Cologne, and is said to have consulted on the construction of that city’s impressive gothic cathedral.

Albert had a consuming interest in studying the natural world and conducted much research into various animals, birds, insects, plants, and minerals. It is from these studies that he has been associated with alchemy and even acclaimed (or slandered) as a practitioner of magic and the occult. He, in fact, limited himself mostly to observation and classification, and did much to debunk more fanciful explanations for the workings of nature. Indeed, he wrote, “The aim of natural science is not to simply accept the statements of others, but to investigate the causes that are at work in nature.” Albert was elected provincial (superior) of the German province of the Dominican Order and was eventually appointed bishop of Ratisbon (Regensburg) an office he resigned after three years. After the death of Saint Thomas Aquinas in 1274, Albert did much to promote and defend the teaching of his illustrious pupil. Albert himself died in 1280 and was canonized and declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius IX in 1931, and proclaimed Patron Saint of natural scientists in 1941.

During his time studying in Germany, Thomas’ fellows, because of his large stature and quiet demeanor, teased him with the nickname “Dumb Ox,” but St. Albert declared that Thomas’ bellows would resound throughout the world. In Cologne, probably at the age of twenty-five, Thomas was ordained to the priesthood.

After a few years, Thomas was sent to Paris to teach his brethren and to earn his own Master of Theology degree (equivalent to today’s doctorate) from the University there. He became embroiled in a controversy, however, and was delayed in receiving his degree and occupying a place on the faculty. When a student was killed by the Paris guard, a dispute erupted between the University and the city of Paris. The University went on strike, but the Dominicans and Franciscans refused to join in. Consequently, St. Thomas and the Franciscan, St. Bonaventure, were refused their Masters’ degrees in Theology. One of the Parisian professors, William of Saint-Amour, even wrote a vicious attack against the friars, The Perils of the Last Times. Thomas responded by writing his own defense of the religious orders, Against Those Attacking the Worship of God and Religion. Finally, Pope Alexander IV and St. Louis IX of France resolved the dispute, and Thomas and Bonaventure received their degrees.

King Louis, indeed, is said to have been an ardent admirer and supporter of Saint Thomas. Once, when the Dominican friar was invited to dine at the table of the king, Brother Thomas fell silent as the meal and conversation continued around him, becoming lost in thought. Then, suddenly, Thomas exclaimed, “That will settle the Manichees!” The other guests stared aghast at the apparently rude outburst. But the king recognized that the brilliant theologian had been distracted wrestling with some philosophical and theological difficulty, apparently trying to answer those who view the material world as evil and deriving from an evil principle (as Manichees do); this issue, of course, is dear to the heart of Dominicans as the preaching of St. Dominic against just such heretics eventually led him to found the Order of Preachers. King Louis accordingly called for scribes to take down the insight Brother Thomas had come to, lest it be forgotten.

In the fifteen years from 1257-1273, St. Thomas was prolific in his writing, teaching, and preaching. He is said to have been able to dictate several different treatises to various scribes at once. Far more than most other professors, Aquinas held a remarkable number of academic disputations throughout the academic year at the University of Paris. The written texts of these public debates have come down to us as Disputed Questions (Quaestiones Disputatae), and Aquinas’s cover an equally impressive range of topics: On Truth, On the Power of God, On Evil, On the Soul, On the Cardinal Virtues, On Spiritual Creatures, among others. In his lifetime he wrote over 50 major works, from original philosophical works, to theological treatises, to commentaries on works of Aristotle and on Scripture. His monumental (yet ultimately unfinished) Summa Theologiae is a masterpiece of medieval scholasticism and Catholic theology.

It is helpful to know something of the details of the form and structure of these writings to be able to profitably read his works. As part of the requirements for earning his Master of Theology degree, Thomas Aquinas lectured on and wrote his Commentary on the Sentences “a collection of doctrinally central, often difficult texts from Scripture and the Church Fathers, compiled by Peter Lombard (d. 1160)” (Jan Aertsen, “Aquinas’s Philosophy in Its Historical Setting,” in The Cambridge Companion to Aquinas, ed. Norman Kretzmann and Eleonore Stump (Cambridge University Press, 1993). p 16). By Aquinas’s time, the Sentences of Peter Lombard had become a standard textbook for theology lectures, and commenting on it was the capstone project for earning the terminal theology degree and license to teach. Aquinas approached this task, however, in a way that departed from the pattern suggested by the text, which Lombard drew from St. Augustine, the 5th century bishop of Hippo (in North Africa), the towering source of much of Catholic theology, as well as from the most important Latin Church Fathers.

On Aquinas’s scheme, things are to be considered according to the pattern of proceeding from God as their source [Trinity, creation, the nature of creatures] and insofar as they return to him as their end [salvation and atonement]. This scheme of exitus and reditus is derived from Neoplatonism and plays a fundamental role in Aquinas’s thought.

Ibid.

The circular theme of creatures exiting from God in love and likewise returning to him recurs in many places in Aquinas’s theological writings, especially in the later of his two great theological syntheses already mentioned, the Summa Theologiae (ST or Summa). (His other monumental synthesis is the Summa contra Gentiles, “written for Dominican missionaries in the Moslem world to make ‘the truth of Catholic faith’ manifest to those who hold beliefs opposed to it.”) (Aertsen, p. 18) Aquinas follows the general exitus/reditus pattern for the Summa Theologiae’s three parts:

- The First Part is the exitus: from God as One and Triune, to creatures, angels and humans;

- The Second Part begins the reditus for humans with his treatment of the moral life, and it has two parts (unimaginatively labeled the First of the Second and Second of the Second);

- Finally, the Third Part completes the reditus with Christ and the Church and her Sacraments.

Additionally, the ST text follows the pattern of the public disputed questions and arranges topics according to general Questions, under which are Articles, subtopic posed in the form of a yes or no question, e.g., Does God exist? (ST I, q. 2, a. 3) – which contains his famous “Five Ways” of proving that God does.) Each article

consists of four parts that begin with fixed formulas:

Ibid, pp. 18-19.

- “It seems it is not so” (Videtur quod non) [There may be several of these, commonly called “Objections” enumerated as Objection 1, Objection 2, etc.]

- “On the contrary” (Sed contra) [Usually one, sometimes two, brief citations of authorities in support of the opposite view, the one Aquinas will argue for. For more on the Sed contra, see below.]

- “I reply that it must be said that” (Respondeo dicendum quod) [Often called the response or “body” (corpus) of the article, this is the longest part and contains Aquinas’s arguments for his answer to the question. Often, his response is not a simple yes or no, but distinguishes what may be yes in a certain respect (secundum quid) from no (or yes) absolutely (simpliciter). It is a common, though difficult to source, dictum characteristic of Thomas Aquinas’s thought that one should never deny, seldom affirm, but always distinguish.]

- Finally, Aquinas offers rejoinders to the objections that were raised at the beginning.” [These are commonly call “Reply to Objection 1, 2, etc.”]

In addition to academic philosophical and theological works, he also wrote poetry in praise of the Eucharist which is still used by the Catholic Church today. Saint Thomas was assigned to the Dominican convent in Orvieto in 1263, while the papal court was also in residence in the central Italian city, when a remarkable Eucharistic miracle occurred. A German priest, Peter of Prague, while on pilgrimage to Rome, stopped in the town of Bolsena to celebrate Mass in the Basilica there. Harboring doubts about the reality of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist, Peter saw the Host miraculously transformed into flesh and blood as he said the words of consecration, blood staining the altar linens of his Mass. The evidence of this miracle was brought for inspection to Pope Urban IV in nearby Orvieto, and as a result, the Roman pontiff commissioned St. Thomas to compose the prayers for Mass and the Divine Office to celebrate the Feast of The Body and Blood of Christ which the pope instituted the following year.

Here is a small but beautiful part of the liturgy St. Thomas composed:

O precious and wonderful banquet that brings us salvation and contains all sweetness! … Yet, in the end, no one can fully express the sweetness of this sacrament, in which spiritual delight is tasted at its very source, and in which we renew the memory of that surpassing love for us which Christ revealed in his passion. It was to impress the vastness of this love more firmly upon the hearts of the faithful that our Lord instituted this sacrament at the Last Supper.

Opusculum 57, in festo Corporis Christi.

He traveled tirelessly around Europe, being called upon alternately by the Papal court and by his Order to teach in Anagni and Orvieto, then in Rome, then in Viterbo.

He was called back to Paris in 1269, however, to help quell another controversy there over the use of Aristotle’s texts and ideas by Christian scholars. Siger of Brabant, a professor on the Faculty of Arts (undergraduate philosophy), had asserted (following the Muslim philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd)) that Aristotle proves that there is one separate intellect for all human persons (and so denying a basis for the immortality of each individual person’s soul), that the world is eternal (and not created a finite time ago as taught in Scripture in Genesis), and that God (in being Self-Thinking Thought) was unaware of the world he causes. Siger and his fellow Heterodox Aristotelians or Latin Averroists, as they came to be called, were even accused of, and condemned for, asserting that there were two truths, one derived from faith and another, contradictory one derived from reason.

Because of the patent incompatibility of certain positions of Averroistic Aristotelianism with the Christian faith (such as the theory of the eternity of the world), some masters of the faculty of arts in thirteenth century Paris developed the theory of double truth: what is established in sacred theology sometimes contradicts what is true in philosophy, so that a Christian philosopher must accept simultaneously two conflicting theses. However, Aquinas strongly opposes this view. Since all truth comes from God, in whom there is no contradiction, such a position is impossible. Apparent contradictions originate from erroneous reasoning or from false deductions from the doctrine of the faith.

Leo J. Elders, SVD, “Faith and Reason: The Synthesis of St. Thomas Aquinas,” Nova et Vetera, English Edition, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2010), p. 529.

Concerned with the threat to the Christian faith posed by these positions and the distortion of Aristotle’s views, as well as the disrepute they cast on the teaching of the ancient Greek’s works, Thomas wrote On the Unity of the Intellect against the Averroists and On the Eternity of the World against the Murmurers, arguing that such positions cannot be supported by reason, nor are they accurate representations of Aristotle’s positions.

Finally, in 1272, he was appointed head of the faculty of theology at the University of Naples. On 6 December 1273, however, he abruptly stopped writing. When his secretary asked him why, Saint Thomas said he had had a vision of God or heaven, after which it seemed to him that all he had written was as straw. (To us not granted such an experience, his writings are nevertheless quite valuable.)

Saint Thomas did not live long after this episode, however. Having been called by Pope Gregory X to attend the Council of Lyons also on the very same day, Thomas traveled as far as Terracina in Central Italy, not far from his family’s estates, before collapsing, possibly striking his head on a low-hanging tree branch. He was first brought to Maenza, to the castle of his niece, Francesca, but he requested to be brought to the nearby Cistercian Monastery of Fossanova, so he might die assisted by the prayers of monks; he lingered there for a month or more. As G. K. Chesterton notes,

It may be worth remarking, for those who think that he thought too little of the emotional or romantic side of religious truth, that he asked to have The Song of Solomon read through to him from beginning to end.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, The Dumb Ox (Image Books 2014, p. 118.

The Song of Solomon (or The Song of Songs (Canticum Canticorum)) is a collection of love poems in the Wisdom literature of the Old Testament having allegorical meaning as declarations of affection, desire, and joy between God and His people Israel; for Christians, these are fulfilled in the marriage of Jesus Christ to His Bride, the Church. The Song of Songs may perhaps have been on Saint Thomas’s mind toward the end of his life. In a late work, Compendium of Theology, possibly composed close to when Saint Thomas stopped writing, he refers to the permanent grasp of lovers in discussing the joy of heaven.

When we see [God] by direct vision [in heaven] we shall hold Him present within ourselves. Thus in The Song of Songs 3:4, the spouse seeks him whom her soul loves; and when at last she finds him she says: “I held him, and I will not let him go.”

Compendium of Theology, Book II, Chapter 9, par. 23.

Saint Thomas died among Cistercian monks on 7 March 1274 at the age of about 50.

Thomas Aquinas was canonized by Pope John XXII on 18 July 1323, and Pope Saint Pius V proclaimed Saint Thomas a Doctor of the Church in 1567. Pope Leo XIII, in the Encyclical Aeterni Patris, recommended the study of Saint Thomas as the model and norm of Christian philosophy. This last endorsement helped to inaugurate the Thomistic revival of the twentieth century.

For a more extensive biography, see this one by D.J. Kennedy.

Other interesting aspects of Saint Thomas’s life and devotion to him and his intercession:

- Feast Day 2021 – Death and Vagaries of His Relics

- Feast Day 2022 – Priest. Preacher, and Poet

- Former Feast Day

- Feast Day 2023 – Angelic Doctor

- Modern Veneration of the Relics of Saint Thomas

- Canonization of Saint Thomas and His Triple Jubilee 2023-2025

- Feast Day 2024 – Jubilee: the Consummation of Love

- The Relics of Saint Thomas Aquinas Come to America

Please support the Thomistic Philosophy Page with a gift of any amount.

Updated November 24, 2024