What the meaning of “IS” is

From his time focusing on material individuals, what we can know of them, and how we know it, Aristotle developed the predicaments or categories of his logic by bringing attention to the different uses we commonly make of the verb “is” or “to be,” for we understand “is” in different ways in “Socrates is a man,” “Socrates is human,” “Socrates is white,” and “White is a color.” These different uses correspond to various logical distinctions, whose neglect led to the confusion among philosophers before Socrates, which Plato’s theory was a valiant, but mostly misguided attempt to solve. (For more on this see Explaining Change in the section on the Philosophy of Nature.)

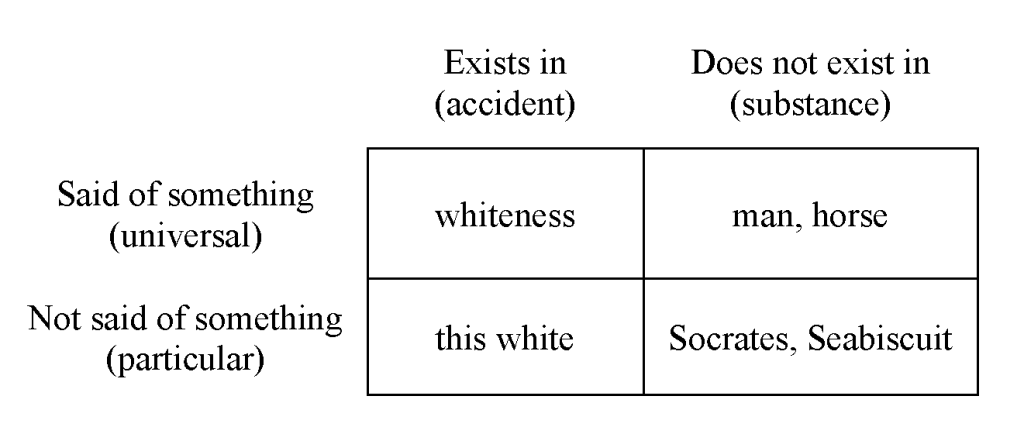

As an example of what Aristotle means, consider what is named by the word “white.” The reality that this word names (a particular color) is not said of a dog, Fido, for instance, in the way that “color” is said of “white.” That is, “this dog is white” does not predicate the color white of the dog, but signifies that the white color exists in the dog, or that the dog has a white color. But when color is said of white, as in “white is a color,” what is meant is that white belongs to the class of colors. Color is the genus, of which white is a species. And the white of this dog, Fido, is a particular instance of the species of white color, just as Fido himself is a particular instance of the species, the universal class, of dogs.

Furthermore, the particular white color exists in “this dog, Fido;” one does not find any “white” except that is in “this dog” or some other thing. This way of speaking can be contrasted with another, for example “This thing is Socrates.” “Socrates” does not name the same kind of reality that “white” does in the previous example. “Socrates” is not said of “this thing” in the same way as “white” is, and “Socrates” does not exist IN “this thing.” Rather, “Socrates” IS “this thing,” and the sentence “this thing is Socrates” asserts an identity between the two realities named.

These basic notions employed in forming proper definitions of things in Aristotle’s logic reflects the basic distinction in the way reality is structured and reflects the basic way that we view reality, indeed how we must view reality if we are to understand it truthfully. The fundamental distinction in both assigning predicables and in the realities so predicated is between substance and accident. What is said of another, i.e., predicated of something, is the universal class to which it belongs, and there are various universal classes of both substances and accidents, and at various levels of universality. Among terms that are said of another, i.e., universals, they may either be a species, which is said of many particular individuals, or a genus, which is said of many species, or of many genera below it. There are universals (genera and species) for both substances and accidents. Fido is an individual, but belongs to the species dog, and to the more general and universal genera: mammal, animal, living thing, material thing; this particular patch of brown exists in Fido, but it is an instance of the color brown, and the more general and universal genera: color, sense quality, quality in general.

Predicaments – The Ten Categories: Substance and Nine Accidents

A particular substance (what does not exist in another and is not said of another) is whatever exists in its own right and belongs to a natural kind (as opposed to artifacts which are collections or arrangements of natural substances). Examples are rocks, trees, animals, etc. What an animal is, a dog for example, is basically the same whether it is black or brown, here or there, etc. A dog is a substance since it exists in its own right; it does not exist in something else, the way a color does. Similarly, there are particular accidents (what exists in but is not said of another) which are modification of a substance: Fido’s particular shade of brown, the pale color of Socrates, etc. (see below).

. . . Socrates is human in a way very different from the way in which he is pale: most immediately and importantly, Socrates could cease to be pale but continue to exist, whereas if he ceased to be human, Socrates would cease to exist altogether. If, that is, Socrates went to the beach and returned sporting a tan, he would still be Socrates. On the other hand, if he went to the beach and were dismembered and eaten by sharks, Socrates would cease to be a human being and so would cease to exist altogether. There are, then, some properties Socrates can afford to lose while remaining in existence, and some properties whose loss would spell his demise.[1]

Accidents, then, are the modifications of substances and they exist in substances. Accidents modify or qualify substances, but accidents do not determine the kind of thing that each substance is. Accidents only exist when they are the accidents of some substance. Thus, things or ‘beings’ naturally fall into ten categories.

Socrates is, therefore, what Aristotle calls a primary substance. What makes him a primary substance is precisely that other things depend upon him for their existence, while he does not depend on anything else.

In fact, Aristotle identifies ten categories of being, each presumably basic, ineliminable, and irreducible to any other kind. These ten are:

Category Example

Substance man, horse

Quantity two feet long

Quality white, grammatical

Relative double, half

Place in the Lyceum, in the market

Time yesterday, a year ago

Position lying, sitting

Having has shoes on, has armor on

Acting upon cutting, burning

Being affected being cut, being burnt[2]

All these distinctions are basically logical, but they reflect the structure of reality. Indeed, Aristotle tells us that the primary sense of substance is the particular individual, and the universal, i.e., genus or species, is substance in a secondary sense. This is because both accidents (white or color in general) and universals (species and genera) only ever exist because the individual particular exists. One never finds any substance of our experience without some accidents, nor an accident that is not the accident of a substance. Every dog, for instance, has some color, place, size. Nevertheless, it is obvious that what a dog is is not the same as its color, or its size, etc. And without particular dogs (Fido, Rover, etc.) there would be no species of dog (in contrast to what Plato who taught that the Form or Idea of Dog-Itself subsists as an objectively existing immaterial universal). In this way, Aristotle clearly opposes the extreme Realism of Plato, though he is still a Realist (as opposed to a Nominalist or Conceptualist) because he thinks that dogs are dogs because they share in the species, or essential nature, of dogs, such nature or form being intrinsic to the dog (not as a separate Form as Plato proposed). (See Explaining Change.)

Substance as individual is the logical and ontological basis for substance as universal, and the individual is the direct and proper object of knowledge; in seeking to understand the world, one seeks to understand and explain the individual material things which make up the world. Universals are the means by which we understand, but they are neither the focus or end of knowledge, nor do they exist except as individuals. This is the opposite view from that held by Plato. For Plato, the universal Form is being in the primary sense because it is the unchanging object of knowledge. Aristotle, by contrast, realizes that the material particular is primary, but that in it, it has an unchanging nature that, apart from its material instantiation, can be known as belonging to, and shared in, universally, i.e., by many individuals. Aristotle thus expanded Plato’s notion of form and recognized the double duty it has to play – first, as a metaphysical principle for the relative stability and actuality in being which things exhibit individually, along with the commonality they share with each other; and, second, as an epistemological principle, i.e., a principle of knowledge, for the stability and universality of knowledge.

Aquinas’s logic and epistemology rest here on his metaphysical realism. He holds that there are real natures of naturally occurring substances and accidents and that these real natures can provide the content for universal categorical propositions. Genuine kind terms refer to real natures, and real definitions explicate these natures by identifying a kind’s genus and specifying differentia (which are also real natures).[3]

[1] Christopher Shields, Ancient Philosophy: A Contemporary Introduction (Routledge 2011), p. 120.

[2] Ibid, p. 122.

[3] Scott MacDonald, “Theory of Knowledge” in The Cambridge Companion to Aquinas, p. 169.

Previous: Logic – Problem of Universals – Return to Logic – Overview – Next: Logic – First and Second Intentions